When Sprinklers Cause the Flood: What Really Happens When Fire Suppression Systems Fail

When people picture a sprinkler system activating, they imagine it saving property from a fire. What they don’t imagine is coming home from the holidays to find a ceiling collapsed and water pouring through the floor, courtesy of the sprinkler system itself.

But that’s exactly what happened in an apartment building I investigated. The fire suppression system worked exactly as designed, until the environment around it didn’t.

When “Protected” Pipes Aren’t Protected

The building utilized a wet fire suppression system, which means the pipes are always filled with water. These systems are common in heated spaces because they provide instant response during a fire. But in this case, the cold air outside the building had become the system’s biggest threat.

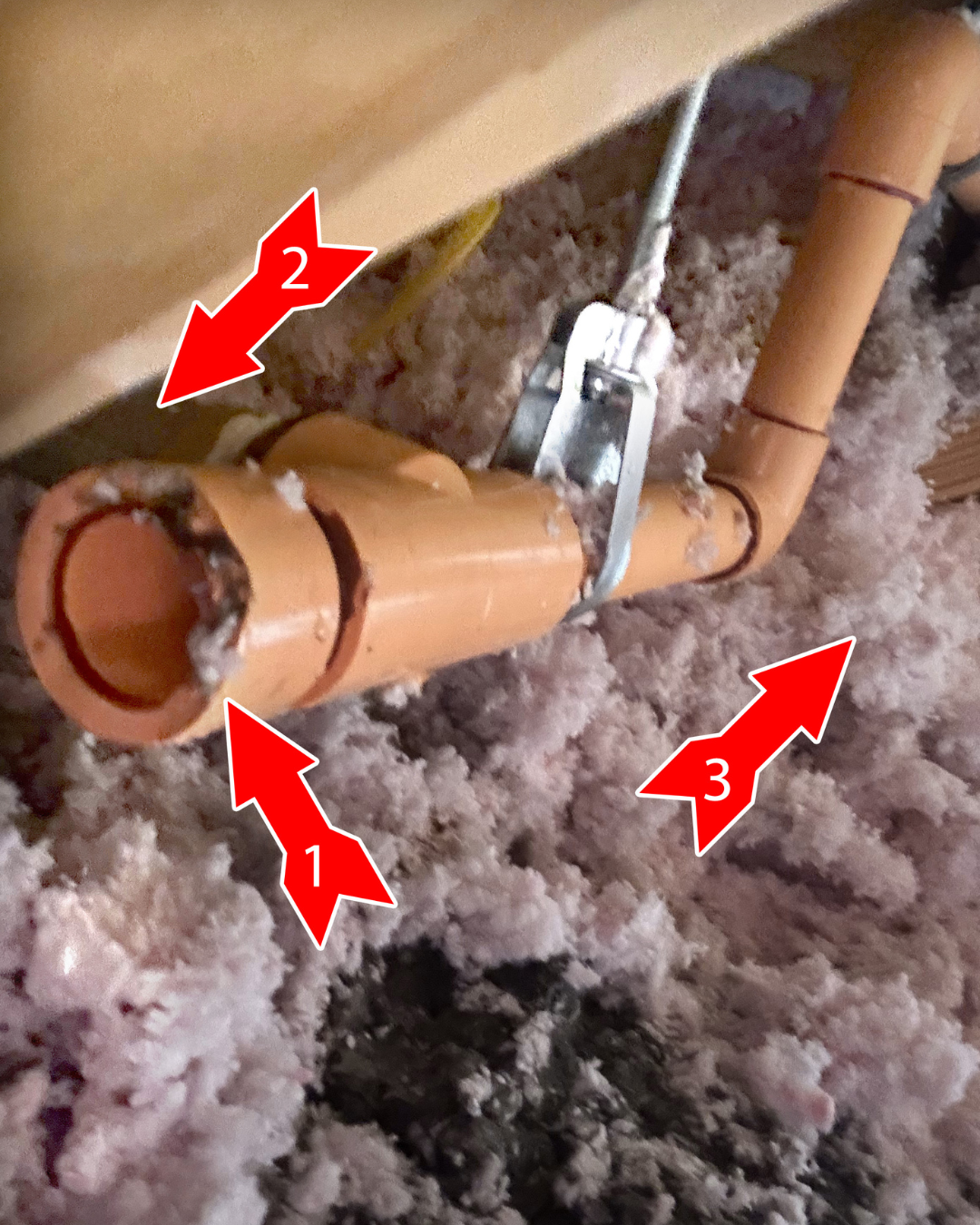

Over the Christmas week, a cold snap hit. Fire suppression pipes located in the ceiling space above a first-floor unit froze and burst, flooding the apartment below. At first glance, it appeared to be a failure of the sprinkler system itself—maybe a maintenance issue or faulty installation. It wasn’t.

The sprinkler piping had been installed correctly, inspected on schedule, and maintained according to code. What failed was the air barrier in the building envelope, the hidden layer meant to keep outdoor air from entering the wall cavity.

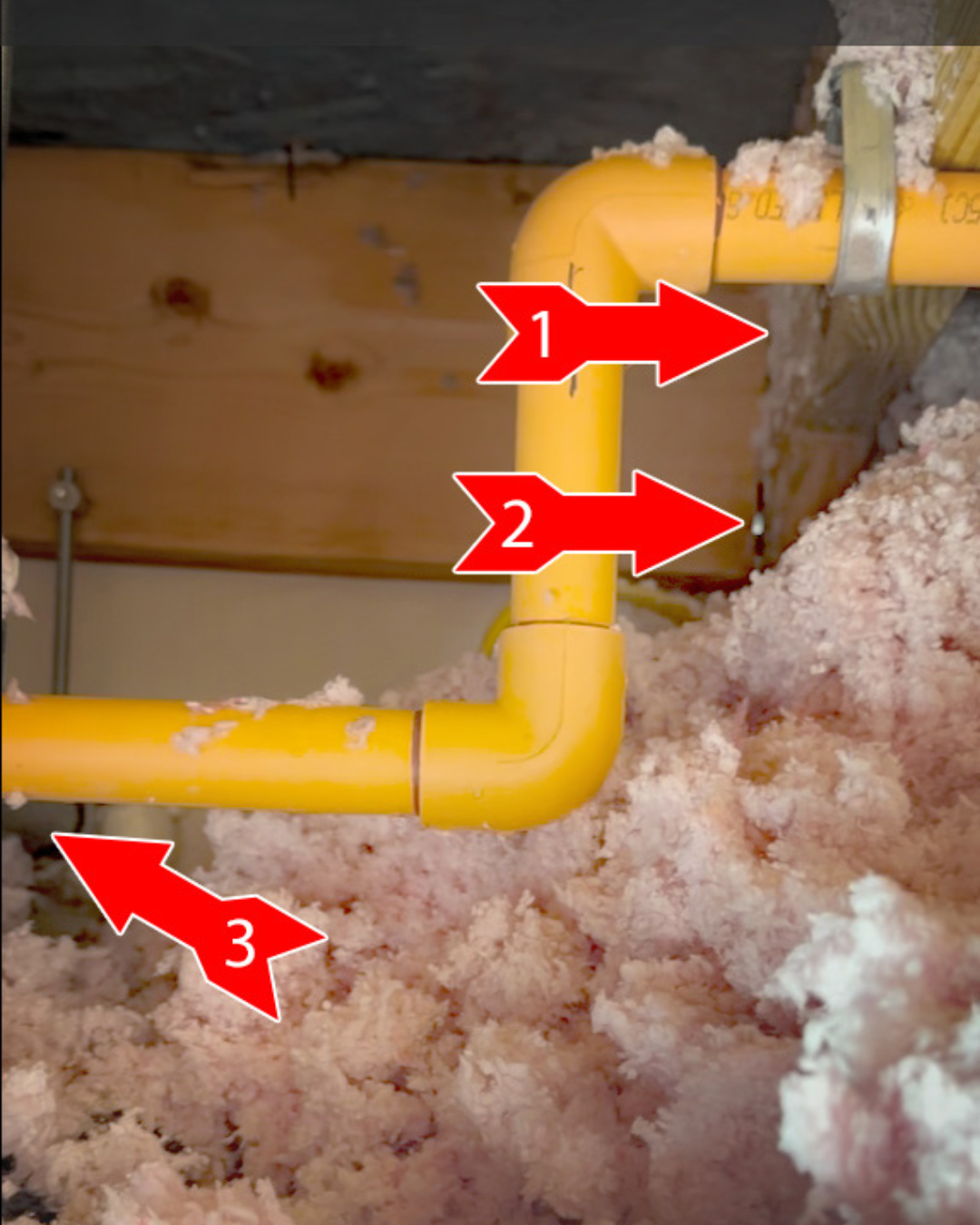

When we examined the space, we found that air could move freely through a gap in the exterior wall sheathing and air barrier. Even though the ceiling was filled with blown-in insulation, according to plan requirements, it wasn’t sealed tightly enough to block cold air that had infiltrated the space from affecting the nearby pipes. The freezing air found its way to the sprinkler lines, which were only about a foot away. When temperatures dropped, it didn’t take long for the trapped water inside those pipes to freeze, expand, and rupture the pipe.

Beyond One Burst Pipe

Not all sprinkler failures are as straightforward as a single frozen line. In other investigations, corrosion or material incompatibility played the leading role.

In a different apartment building, a sprinkler head installed through a black steel bushing had been connected to copper piping. With stagnant water sitting in the system for more than two decades, galvanic corrosion formed at the joint between the two metals. Over time, it ate through the connection, causing a slow leak that led to significant flooding.

In another situation, the cause was more subtle: a sprinkler head located in an unconditioned attic failed due to solder creep, a gradual weakening of the heat-sensitive metal that seals the sprinkler head. Repeated heating and cooling cycles in the attic caused the solder to soften and reform until it could no longer hold back water pressure. No fire, no smoke—just a slow leak from long-term creep.

In dry sprinkler systems, where the pipes are filled with compressed air instead of water, failures often occur when the air compressor stops working or after maintenance crews forget to drain the pipes. The result is the same: water where it shouldn’t be.

What These Failures Have in Common

Across all of these cases, the lesson is consistent: sprinkler systems rarely fail in isolation. They’re deeply connected to their environment—the building envelope, the materials used, and the maintenance practices in place.

When a system floods a space, it’s easy to point to the sprinkler head or valve as the culprit. But the real cause often lies a few feet—or even a few decisions—away. That’s where forensic engineering comes in: tracing how temperature, materials, and design interact until the exact failure point becomes clear.

About the Author

John M. Rophael, P.E., is a mechanical consulting engineer at EDT Forensic Engineering and Consulting. He applies more than a decade of experience to evaluate the root cause of mechanical and piping system failures and to provide consultation related to HVAC systems, plumbing, mechanical design, damage assessment, and code interpretation.